| [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] |

LilyPond — Esszé

|

Ez az esszé a LilyPond 2.23.82 automatikus kottaszedési mechanizmusmába nyújt mélyebb betekintést. |

| 1. A kottaszedés | ||

| 2. Irodalomjegyzék | ||

| A. GNU Free Documentation License | E dokumentum licence. | |

| B. LilyPond tárgymutató |

|

A teljes dokumentáció a https://lilypond.org/ honlapon található. |

| [ << Top ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Top ] | [Fel: Top ] | [ A LilyPond története > ] |

1. A kottaszedés

Ez az esszé leírja, miért született a LilyPond, és hogyan képes ilyen gyönyörű kottákat előállítani.

| 1.1 A LilyPond története | ||

| 1.2 A kottaszedés fortélyai | ||

| 1.3 Az automatizált kottaszedés | ||

| 1.4 Building software | ||

| 1.5 Putting LilyPond to work | ||

| 1.6 Engraved examples (BWV 861) |

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < A kottaszedés ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés ] | [ A kottaszedés fortélyai > ] |

1.1 A LilyPond története

Mielőtt a LilyPondot koncerteken használt csodaszép kották szedésére kezdtük volna használni, mielőtt zenetudományi dokumentumok zenei idézeteit vagy akár egyszerű dallamokat le lehetett volna vele kottázni, mielőtt szerte a világon a felhasználók széles körben kezdték volna használni, vagy ez az esszé megszületett volna, a LilyPond története egy kérdéssel kezdődött:

Miért nem adják vissza a számítógép által szedett kották a kézzel szedett kották szépségét és kiegyensúlyozottságát?

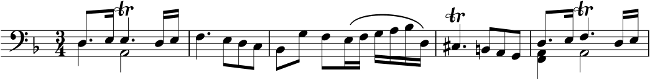

Erre többnyire választ kaphatunk, ha górcső alá vesszük a következő két kottát. Az első példa egy gondosan kézzel szedett kotta 1950-ből, a második egy modern, számítógéppel szedett kiadás.

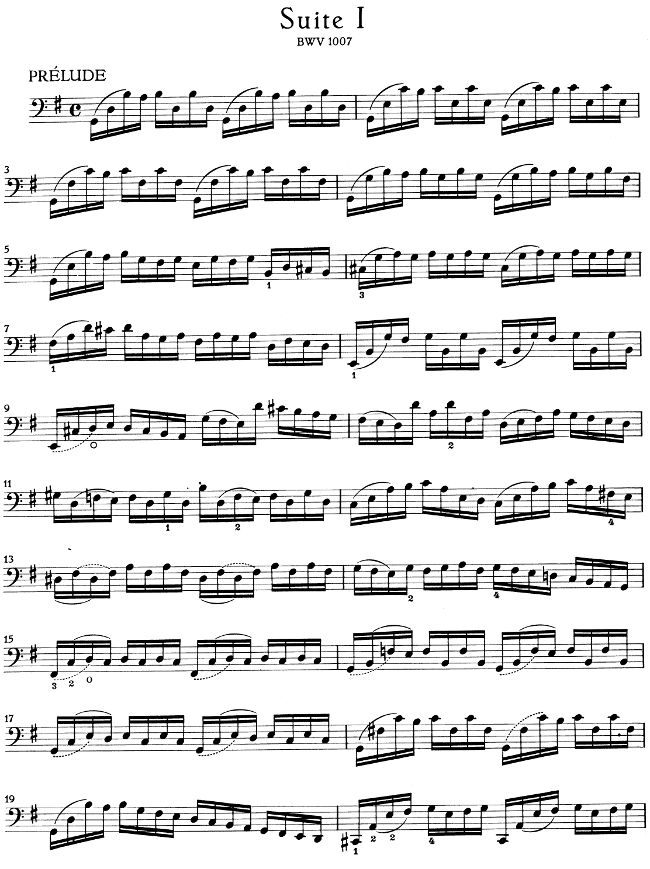

Bärenreiter BA 320, ©1950:

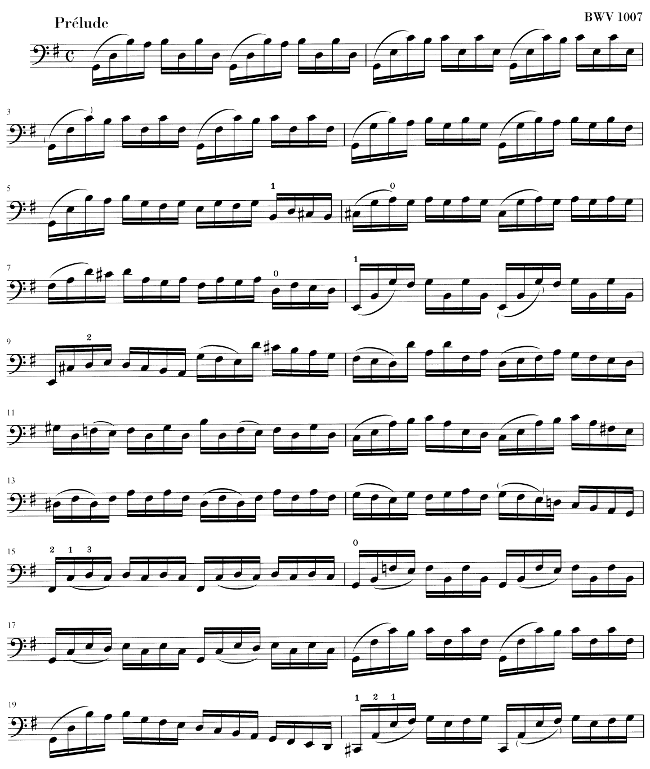

Henle no. 666, ©2000:

J. S. Bach első, csellóra írt szólószvitjének két kiadása hangról hangra megegyezik, mégis megjelenésükben merőben különbözőek, különösen, ha kinyomtatjuk és megszokott távolságból szemléljük őket. Próbáljuk meg mindkét kottapéldát elolvasni, illetve játszani belőlük, és meg fogjuk állapítani, hogy a kézzel szedett kotta használata kellemesebb. Folyékonysága és dinamikája egy élő, lélegző zenemű érzetét kelti, miközben az újabb kiadás hidegnek és mechanikusnak hat.

Nehéz egyből észrevenni, miben rejlik a különbség a kották között. Az új kotta első ránézésre rendezett és pontos, talán még „jobb” is, mivel számítógéphez illőbb és egységes a megjelenése. Ez gondolkodóba ejtett minket egy időre. Javítani akartunk a számítógép által szedett kottaképen, de ehhez előbb rá kellett jönnünk, mi volt a gond vele.

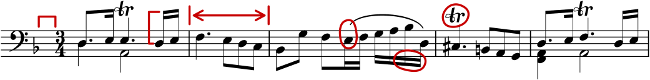

A válasz az új kotta precíz, matematikai pontosságú egyformaságában rejlik. Keressük csak meg minden sor közepén az ütemvonalakat: a kézzel szedett változatban az ütemvonalak elhelyezkedése természetes módon változik, míg a számítógép szinte pontosan egymás alá, középre szedte őket. Ezt mutatja be a következő egyszerűsített ábra, melyen a kézzel (balra), ill. a komputerrel szedett változat (jobbra) elrendezése látható:

A számítógép által előállított szedésben még az egyes kottafejek is függőlegesen egymáshoz lettek igazítva, ami azt az érzetet kelti, mintha a dallamvonal eltűnne egy szimbólumokból álló merev rács mögött.

További különbségek is vannak: a kézzel szedett változat függőleges vonalai erősebbek, a kötőívek szorosabban tapadnak a kottafejekhez, és a gerendák szögeiben is nagyobb változatosság figyelhető meg. Noha az ilyen részletes elemzés szőrszálhasogatásnak tűnhet, végeredménye egy olyan kotta, ami egyszerűbben olvasható. A számítógépes kottában minden sor szinte egyforma, és ha a zenész egy pillanatra máshová tekint, hamar elveszítheti a tájékozódást az oldalon.

A LilyPond megalkotásának célja az volt, hogy kiküszöböljük a többi kottaszedő szoftver szépséghibáit, és segítségével olyan kottákat lehessen előállítani, melyek szépsége a legigényesebb kézzel szedett kottákéval vetélkedik.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < A LilyPond története ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés ] | [ A kottában használt betűtípusok > ] |

1.2 A kottaszedés fortélyai

A zeneművek nyomdai előkészítését kottaszedésnek nevezik. Ez a kifejezés a kották nyomtatásának hagyományos, kézi módszerére utal.1 Ez a folyamat még a 20. században első felében is úgy nézett ki, hogy a kotta elemeit kivágták, majd tükrözve belemélyesztették egy cink- vagy ónlemezbe. A lemezre ezután festéket hordtak fel, és a festék a bemélyedésekben maradt. A lemez a papírra rányomva a kotta képét adta. A metszést teljesen kézzel végezték, és bárminemű javítás nagyon körülményes volt, így a kottakép elsőre tökéletes kellett, hogy legyen. A kottaszedés tudománya nagyon különleges szakma, ahol a kézművesnek körülbelül öt éves képzést kellett elvégeznie, mielőtt a mester címet kérvényezhette. További öt év volt szükséges ahhoz, hogy a szakma minden csínját-bínját valóban magáénak tudhassa.

A LilyPond megalkotását azok a kézzel szedett kották inspirálták, amelyeket a 20. század közepe felé az európai kottakiadók (többek között Bärenreiter, Duhem, Durand, Hofmeister, Peters és Schott) hoztak forgalomba. Munkásságukat bizonyos szempontból a hagyományos kottaszedés csúcsának lehet tekinteni. Kiadványaik tanulmányozásával rengeteget tanultunk arról, mik az ismertetőjelei egy szép tipográfiájú kottának, és milyen szempontokat szeretnénk a LilyPonddal utánozni.

| A kottában használt betűtípusok | ||

| Optikai kiegyenlítettség | ||

| Pótvonalak | ||

| Optikai nagyság | ||

| Miért szükséges ez a nagy felhajtás? |

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < A kottaszedés fortélyai ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés fortélyai ] | [ Optikai kiegyenlítettség > ] |

A kottában használt betűtípusok

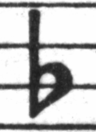

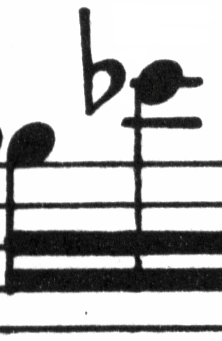

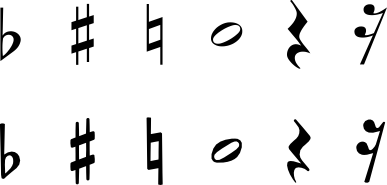

A lenti ábra jól mutatja a különbséget egy hagyományosan és egy számítógép által szedett kottaelem közt. A bal oldali képen egy beszkennelt b módosítójel látható egy kézi Bärenreiter kiadásból, míg a jobb oldali ugyanennek a zeneműnek 2000-ben kiadott változatából származik. Noha mindkét képet ugyanolyan árnyalatú tintával nyomtatták, a régebbi verzió sötétebb: a kottasorok vonalai vastagabbak, és a Bärenreiter b-je gömbölyded, majdhogynem érzékien kerek. A jobb oldali kép vonalai ezzel szemben vékonyabbak, elrendezése szögletes, sarkai élesek.

|  | |

| Bärenreiter (1950) | Henle (2000) |

Amikor úgy döntöttük, hogy írunk egy kottaszedő programot, nem volt olyan, szabad felhasználású zenei betűtípus, ami jól passzolt volna kedvenc kottáink elegáns kottaképéhez. Ezen felbuzdulva megalkottunk egy zenei szimbólumokból álló betűtípust, amely a kézzel szedett kották szemrevaló kinézetét veszi alapul. A betűtípus megtervezése során szerzett tapasztalatok nélkül soha nem ismertük volna fel, milyen csúnyák is azok a betűtípusok, amiket eleinte csodáltunk.

Lent két zenei betűkészletre láthatunk példát: a felső a Sibelius alapbeállítású készlete (Opus), az alsó a LilyPondé.

A LilyPond kottaelemei vastagabbak, valamint vastagságuk konzisztensebb, ami miatt jóval egyszerűbb az olvasásuk. A vonalaknak, mint például a negyed szünet szárnyai, nem hegyes végük van, hanem finoman legömbölyített. Ennek oka, hogy a hegyes végek a hagyományos nyomóformán nagyon törékenyek, és a használat közben gyorsan elkopnak. Összefoglalva, a jelkészlet teltségét gondosan össze kell hangolni a vonalak (gerendák, ívek) vastagságával, hogy erős, mégis kiegyensúlyozott összképet kapjunk.

Vegyük észre továbbá, hogy a félkotta feje nem ellipszis, hanem enyhén rombusz alakú. A b módosítójel függőleges szára felfelé némileg kiszélesedik. A keresztet és a feloldójelet egyszerűbb távolról megkülönböztetni, mert ferde vonalaiknak eltérő a dőlésszöge, illetve függőleges vonalaik különböző vastagságúak.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < A kottában használt betűtípusok ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés fortélyai ] | [ Pótvonalak > ] |

Optikai kiegyenlítettség

A kották vízszintes elrendezésénél a mindenkori hangjegy hosszúságának kell visszatükröződnie. Amint a fenti Bach-szvit példáján már megfigyelhettük, sok modern kottánál a hangjegyek hosszának ábrázolása a matematikai precizitás felé törekszik, ami nem túl szép eredményhez vezet. A következő példában bemutatjuk Önöknek ugyanazt a motívumot kétszer: először matematikai pontossággal, másodszor ugyanezt kijavítva. Melyik példa tetszik Önnek jobban?

Ezen kottarészlet egyforma hosszúságú hangjegyeket használ. A hangjegyek közti távolságnak tükröznie kellene ezt. Sajnos a szemünk becsap: nem csak az egymást követő kottafejek távolságát kell figyelembe kell venni, hanem a szárukat is. Tehát egymás után következő fölfelé-lefelé szárú hangjegyeket kicsit távolabb kell helyezni egymástól, míg a lefelé-fölfelé kombináció szűkebb távolságot kíván, és az egész még függ a hangjegyek függőleges pozíciójától. Az alsó példa ezeket a korrektúraelveket tükrözi. Ellenben a felső példán a hangjegyek alsó-felső irányba váltakozása olyan érzetet kelt, mintha összegubancolódtak volna. Az alsó példa ezeket a szabályokat tükrözi. Ellenben a felső példa az olvasó szemében olyan érzetett kelt, mintha alul-fölül a kottafejek egy csomóban lennének. Egy kottaszedő mester ezt a beosztást úgy igazítaná el, hogy annak az olvasása kellemes legyen.

A Lilypond beosztásért felelős algoritmusa úgy kalkulál, hogy az ütemvonalat is figyelembe veszi, ami miatt az utolsó hangjegy a fenti példában több helyet kap, ezért nem kelti a zsúfoltság hatását. Egy szár lent nem szorulna erre a beosztásra.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Optikai kiegyenlítettség ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés fortélyai ] | [ Optikai nagyság > ] |

Pótvonalak

A pót- (esetleg: segéd-) vonalak mindig kihívás elé állítják a tipográfiát: miattuk nehezebb a hangjegyeket sűrűn elrendezni és a hangmagasságot egy gyors pillantással meg kell tudni állapítani. A lentebb található példában láthatjuk, hogy a pótvonalnak vastagabbnak kell lennie mint egy normál kottavonalnak és egy tanult kottaszedő a pótvonalat lerövidíti azért, hogy a módosító jeleknek maradjon hely. Ezt a tulajdonságot mi beleépítettük a Lilypondba.

|  |

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Pótvonalak ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés fortélyai ] | [ Miért szükséges ez a nagy felhajtás? > ] |

Optikai nagyság

A kottákat különböző méretben nyomják. Eredetileg ehhez különböző méretű kliséket gyártottak, ami egyben azt jelenti, hogy minden klisé olyan minőségű volt, hogy a saját méretében a legideálisabb képet adja. A digitális fonttal tudjuk a hangjegyek kontúrját matematikusan felnagyítani illetve kicsinyíteni azért, hogy a tetszés szerinti méretben elő tudjuk állítani, aminek sok előnye van. Azonban kis méretben a szimbólumok túl vékonynak hatnak.

A Lilypond számára különböző vastagságú szedéstípusokat készítettünk, melyek egy bizonyos kottaméretnek felelnek meg. Az itt látható Lilypond kottaszedés 26-os méretű:

Itt ugyanazok a kották 11-es méretben, utána 236%-al nagyítva. hogy a kép pontosan abban a méretben jelenjen meg, mint az előbbi.

Kisebb méretnél a Lilypond arányosan vastagított kottavonalakat használ a kitűnő olvashatóság érdekében.

Ez teszi lehetővé különböző méretű kottasorok békés egymás mellett élését egy oldalon:

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Optikai nagyság ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés fortélyai ] | [ Az automatizált kottaszedés > ] |

Miért szükséges ez a nagy felhajtás?

Musicians are usually more absorbed with performing than with studying the looks of a piece of music, so nitpicking typographical details may seem academic. But it is not. Sheet music is performance material: everything is done to aid the musician in letting her perform better, and anything that is unclear or unpleasant to read is a hindrance.

Traditionally engraved music uses bold symbols on heavy staff to create a strong, well-balanced look that stands out well when the music is far away from the reader: for example, if it is on a music stand. A careful distribution of white space allows music to be set very tightly without crowding symbols together. The result minimizes the number of page turns, which is a great advantage.

This is a common characteristic of typography. Layout should be pretty, not only for its own sake, but especially because it helps the reader in his task. For sheet music this is of double importance because musicians have a limited amount of attention. The less attention they need for reading, the more they can focus on playing the music. In other words, better typography translates to better performances.

These examples demonstrate that music typography is an art that is subtle and complex, and that producing it requires considerable expertise, which musicians usually do not have. LilyPond is our effort to bring the graphical excellence of hand-engraved music to the computer age, and make it available to normal musicians. We have tuned our algorithms, font-designs, and program settings to produce prints that match the quality of the old editions we love to see and love to play from.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Miért szükséges ez a nagy felhajtás? ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés ] | [ Szépségverseny > ] |

1.3 Az automatizált kottaszedés

Ebben a szakaszban arról lesz szó, mi szükséges egy program megírásánál, ami az elkészült kotta szedéstükrét meghatározza. Egy módszer ami elmagyarázza a számítógépnek a szép szedéstükör ismérveit és részletesen összehasonlítja a hagyományos módon előállított kottával.

| Szépségverseny | ||

| A minőség javítása a kottaképek összehasonlításával | ||

| Mindent szépen elrendezünk |

Szépségverseny

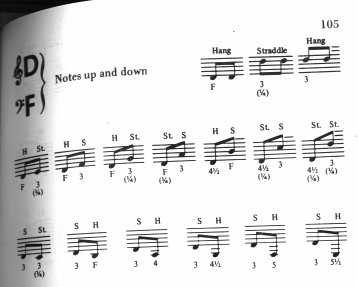

Hogyan kell hát a tipográfiát felhasználnunk? Másképpen mondva: A három egymást követő kötőívből melyiket válasszuk ki?

Sajnos kevés könyv állt rendelkezésünkre a kottaszedés művészetéről. Így csak ökölszabályokat állíthattunk fel és egyes példákat tudunk bemutatni. Ezek a szabályok ugyan informatívak lehetnek de túl messze távolodnak attól az algoritmustól, amit a programba beépítünk. Ahol a felhasznált irodalom által kívánt szabályokat felhasználtuk, az algoritmust nagyon sok manuális beállítás befolyásolja. Minden lehetséges esetet kielemezni nagy munka lenne és legtöbbször nem meríti ki az összes lehetőséget:

(Kép forrása: Ted Ross, The Art of Music Engraving)

Ahelyett, hogy megpróbálkoznánk azzal, hogy minden lehetséges esethez egy hozzá pontosan felvázolni, hogy a legtetszetősebbet ki tudja választani a szoftver. Utána felállítunk a lehetséges változatokból egy „csúnyasági ranglistát” és kiválasztjuk a legkevésbé csúnyát.

Például itt a legátó ívet 3 lehetséges pályán rajzolta fel és mindegyik változat rondaságát pontozta a program. Az első példa 15,39 pontot kapott mert az ív félbevágott egy kottafejet.

A második példa már szebb, de az ív végei nem érintik sem a kezdő sem a befejező hang bogyóját. Ebben az esetben 1,71 pontot kap a bal 9,37 pontot a jobb oldal és további két pontot mivel az ív felfelé tart miközben a dallam ereszkedik. Összesen 13,08 pont:

Az utolsó ív 10,04 pontot kap mivel jobb oldalon hagyott egy rést és 2 pontot a fent található lejtésért/emelkedésért tehát a három közül ez a legszebb.

Ez a technika teljesen általános és felhasználja a program az optikai kinézet javításáért különböző ívek összekombinálásánál kötőíveknél, pontok elhelyezésénél, akkordoknál illetve sor és oldaltöréseknél. Ezeknek a döntéseknek az eredményeit össze tudjuk vetni a kézzel szedett kották kinézetével.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Szépségverseny ] | [Fel: Az automatizált kottaszedés ] | [ Mindent szépen elrendezünk > ] |

A minőség javítása a kottaképek összehasonlításával

A Lilypond újabb verziói lépésről-lépésre jobbak lettek miközben folyamatosan a kézzel szedett kottákkal lettek összehasonlítva.

Itt látható egy kézzel szedett referenciapélda:

és ugyanez a sor így néz ki a Lilypond egyik régi verziójával (1.4-es verzió 2001 május):

A Lilypond 1.4-es kiadása minden esetre olvashatóbb de egy részletes összevetés az eredetivel a formázás sok apró hibájára mutat rá:

- Az ütemmutató előtt nincs elég hely

- A gerendás hangjegyek szárai túl hosszúak

- A második és negyedik ütem túl keskeny

- A kötőívek idétlenek

- A trillajel túl nagy

- A szárak vékonyak

(Ezenkivül van még két hiányzó kottafej, több hiányzó közreadói megjegyzés és egy fals hangmagasság!)

Igazítva az oldalkinézeti szabályokon és a betűtípusdizájnon az újabb kiadások rendkívül sokat javultak. Hasonlítsa össze ugyanazt a referenciapéldát az aktuális Lilypond verzióval (2.23.82):

Az aktuális kiadás ugyan még nem a referencia klónja, de jobban megközelíti már a nyomdai minőséget.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < A minőség javítása a kottaképek összehasonlításával ] | [Fel: Az automatizált kottaszedés ] | [ Building software > ] |

Mindent szépen elrendezünk

A Lilypond képességeit mérhetjük avval is, hogy összehasonlítjuk a kereskedelemben kapható programokkal. Ebben az esetben a Finale 2008-at vettük, egyike a legismertebb kottaszedő programoknak különösen Észak-Amerikában. A Sibelius a Finale fő vetélytársa, legfőképp Európában ismert.

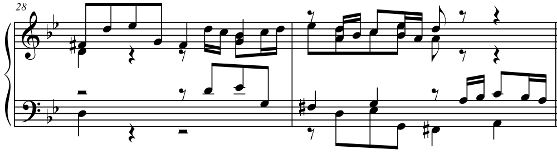

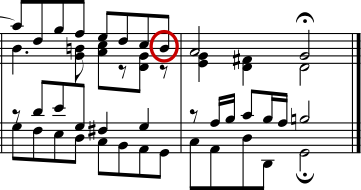

Összehasonlításunkhoz a Wohltemperiertes Clavier I. kötetének g-moll fúgáját (BWV 861) választottuk, melynek nyitótémája:

Összehasonlításunkban a darab utolsó 7 ütemét írtuk meg Finale és a Lilypond segítségével. Ez az a pont, ahol a téma háromszólamú szűkmenetben tér vissza és megy át a zárószakaszba. A Finale verziónál ellenálltunk a kísértésnek, hogy a normáltól eltérő dolgokat korrigáljuk, mivel meg akarjuk mutatni azokat a dolgokat, amit ezek a programok külön beavatkozás nélkül rendesen csinálnak meg. Az egyetlen változtatás csak a méretnél volt, hiszen hozzáigazítottuk ennek az esszének az oldalméretéhez, valamint két sorra korlátoztuk a kottát annak érdekében, hogy az összehasonlítás egyszerűbb legyen. Alapértelmezett beállításoknál a Finale két háromütemes sort és egy záró teljes szélességű, csak egy ütemet tartalmazó sort állítana elő.

Rengeteg különbség van a két kotta között: először a Finale, majd a Lilypondé látható:

Pár hiba a teljesség igénye nélkül, amit a külön nem szerkesztett Finale szedés tartalmaz:

- A legtöbb gerenda túl messzire távolodik a kottasortól. A gerenda, ami a a rendszer közepére mutat, általában oktáv hosszúságú kellene legyen, de a kottaszedő lekurtítja azt, ha a gerendák polifónia esetén kilógnak. A Finale gerendázásért felelős egységét a programban található Patterson Beams Plugin tudja feljavítani, de ezt a lépést ennél a példánál elhagytuk.

- A Finale nem találja meg a szorosan egymáshoz illeszkedő hangjegyek helyét, ezért a kotta nehezen olvasható, főleg ha az alsó és felső szólam időlegesen helyet cserél.

- A Finale minden szünetjelet pontosan ugyanabba az állásba pozicionál. Kézzel állíthatók ugyan szükség esetén, de a program nem figyel a másik szólamra. Most ugyan nem esik egyik szólambeli hang másik szólambeli szünetre, de ez tisztán véletlen: a megírt hangmagasságokból adódik, nem a szünetek elhelyezéséből. Mondhatni, az ütközések elkerülése Bach érdeme, nem a Finalé-é.

This example is not intended to suggest that Finale cannot be used to produce publication-quality output. On the contrary, in the hands of a skilled user it can and does, but it requires skill and time. One of the fundamental differences between LilyPond and commercial scorewriters is that LilyPond hopes to reduce the amount of human intervention to an absolute minimum, while other packages try to provide an attractive interface in which to make these types of edits.

One particularly glaring omission we found from Finale is a missing flat in measure 33:

The flat symbol is required to cancel out the natural in the same measure, but Finale misses it because it occurred in a different voice. So in addition to running a beaming plug-in and checking the spacing on the noteheads and rests, the user must also check each measure for cross-voice accidentals to avoid interrupting a rehearsal over an engraving error.

If you are interested in examining these examples in more detail, the full seven-measure excerpt can be found at the end of this essay along with four different published engravings. Close examination reveals that there is some acceptable variation among the hand-engravings, but that LilyPond compares reasonably well to that acceptable range. There are still some shortcomings in the LilyPond output, for example, it appears a bit too aggressive in shortening some of the stems, so there is room for further development and fine-tuning.

Of course, typography relies on human judgment of appearance, so people cannot be replaced completely. However, much of the dull work can be automated. If LilyPond solves most of the common situations correctly, this will be a huge improvement over existing software. Over the course of years, the software can be refined to do more and more things automatically, so manual overrides are less and less necessary. Where manual adjustments are needed, LilyPond’s structure has been designed with that flexibility in mind.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Mindent szépen elrendezünk ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés ] | [ Music representation > ] |

1.4 Building software

This section describes some of the programming decisions that we made when designing LilyPond.

| Music representation | ||

| What symbols to engrave? | ||

| Flexible architecture |

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Building software ] | [Fel: Building software ] | [ What symbols to engrave? > ] |

Music representation

Ideally, the input format for any high-level formatting system is an abstract description of the content. In this case, that would be the music itself. This poses a formidable problem: how can we define what music really is? Instead of trying to find an answer, we have reversed the question. We write a program capable of producing sheet music, and adjust the format to be as lean as possible. When the format can no longer be trimmed down, by definition we are left with content itself. Our program serves as a formal definition of a music document.

The syntax is also the user-interface for LilyPond, hence it is easy to type:

{

c'4 d'8

}

to create a quarter note on middle C (C1) and an eighth note on the D above middle C (D1).

On a microscopic scale, such syntax is easy to use. On a larger scale, syntax also needs structure. How else can you enter complex pieces like symphonies and operas? The structure is formed by the concept of music expressions: by combining small fragments of music into larger ones, more complex music can be expressed. For example

f4

Simultaneous notes can be constructed by enclosing them with

<< and >>:

<<c4 d4 e4>>

This expression is put in sequence by enclosing it in curly braces

{ … }:

{ f4 <<c4 d4 e4>> }

The above is also an expression, and so it may be combined again

with another simultaneous expression (a half note) using

<<, \\, and >>:

<< g2 \\ { f4 <<c4 d4 e4>> } >>

Such recursive structures can be specified neatly and formally in a context-free grammar. The parsing code is also generated from this grammar. In other words, the syntax of LilyPond is clearly and unambiguously defined.

User-interfaces and syntax are what people see and deal with most. They are partly a matter of taste, and also the subject of much discussion. Although discussions on taste do have their merit, they are not very productive. In the larger picture of LilyPond, the importance of input syntax is small: inventing neat syntax is easy, while writing decent formatting code is much harder. This is also illustrated by the line-counts for the respective components: parsing and representation take up less than 10% of the source code.

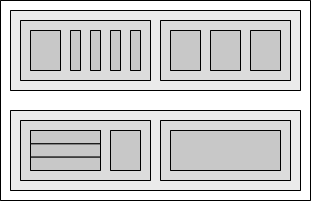

When designing the structures used in LilyPond, we made some different decisions than are apparent in other software. Consider the hierarchical nature of music notation:

In this case, there are pitches grouped into chords that belong to measures, which belong to staves. This resembles a tidy structure of nested boxes:

Unfortunately, the structure is tidy because it is based on some excessively restrictive assumptions. This becomes apparent if we consider a more complicated musical example:

In this example, staves start and stop at will, voices jump around between staves, and the staves have different time signatures. Many software packages would struggle with reproducing this example because they are built on the nested box structure. With LilyPond, on the other hand, we have tried to keep the input format and the structure as flexible as possible.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Music representation ] | [Fel: Building software ] | [ Flexible architecture > ] |

What symbols to engrave?

The formatting process decides where to place symbols. However, this can only be done once it is decided what symbols should be printed – in other words, what notation to use.

Common music notation is a system of recording music that has evolved over the past 1000 years. The form that is now in common use dates from the early Renaissance. Although the basic form (i.e., note heads on a 5-line staff) has not changed, the details still evolve to express the innovations of contemporary notation. Hence, common music notation encompasses some 500 years of music. Its applications range from monophonic melodies to monstrous counterpoints for a large orchestra.

How can we get a grip on such a seven-headed beast, and force it

into the confines of a computer program? Our solution is to break

up the problem of notation (as opposed to engraving, i.e.,

typography) into digestible and programmable chunks: every type of

symbol is handled by a separate module, a so-called plug-in. Each

plug-in is completely modular and independent, so each can be

developed and improved separately. Such plug-ins are called

engravers, by analogy with craftsmen who translate musical

ideas to graphic symbols.

In the following example, we start out with a plug-in for note

heads, the Note_heads_engraver.

Then a Staff_symbol_engraver adds the staff,

the Clef_engraver defines a reference point for the staff,

and the Stem_engraver adds stems.

The Stem_engraver is notified of any note head coming

along. Every time one (or more, for a chord) note head is seen, a

stem object is created and connected to the note head. By adding

engravers for beams, slurs, accents, accidentals, bar lines, time

signature, and key signature, we get a complete piece of notation.

This system works well for monophonic music, but what about polyphony? In polyphonic notation, many voices can share a staff.

In this situation, the accidentals and staff are shared, but the stems, slurs, beams, etc., are private to each voice. Hence, engravers should be grouped. The engravers for note heads, stems, slurs, etc., go into a group called ‘Voice context’, while the engravers for key, accidental, bar, etc., go into a group called ‘Staff context’. In the case of polyphony, a single Staff context contains more than one Voice context. Similarly, multiple Staff contexts can be put into a single Score context. The Score context is the top level notation context.

Lásd még

Internals Reference: Contexts.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < What symbols to engrave? ] | [Fel: Building software ] | [ Putting LilyPond to work > ] |

Flexible architecture

When we started, we wrote the LilyPond program entirely in the C++ programming language; the program’s functionality was set in stone by the developers. That proved to be unsatisfactory for a number of reasons:

- When LilyPond makes mistakes, users need to override formatting decisions. Therefore, the user must have access to the formatting engine. Hence, rules and settings cannot be fixed by us at compile-time but must be accessible for users at run-time.

- Engraving is a matter of visual judgment, and therefore a matter of taste. As knowledgeable as we are, users can disagree with our personal decisions. Therefore, the definitions of typographical style must also be accessible to the user.

- Finally, we continually refine the formatting algorithms, so we need a flexible approach to rules. The C++ language forces a certain method of grouping rules that cannot readily be applied to formatting music notation.

These problems have been addressed by integrating an interpreter for the Scheme programming language and rewriting parts of LilyPond in Scheme. The current formatting architecture is built around the notion of graphical objects, described by Scheme variables and functions. This architecture encompasses formatting rules, typographical style and individual formatting decisions. The user has direct access to most of these controls.

Scheme variables control layout decisions. For example, many graphical objects have a direction variable that encodes the choice between up and down (or left and right). Here you see two chords, with accents and arpeggios. In the first chord, the graphical objects have all directions down (or left). The second chord has all directions up (right).

The process of formatting a score consists of reading and writing the variables of graphical objects. Some variables have a preset value. For example, the thickness of many lines – a characteristic of typographical style – is a variable with a preset value. You are free to alter this value, giving your score a different typographical impression.

Formatting rules are also preset variables: each object has variables containing procedures. These procedures perform the actual formatting, and by substituting different ones, we can change the appearance of objects. In the following example, the rule governing which note head objects are used to produce the note head symbol is changed during the music fragment.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Flexible architecture ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés ] | [ Engraved examples (BWV 861) > ] |

1.5 Putting LilyPond to work

We have written LilyPond as an experiment of how to condense the art of music engraving into a computer program. Thanks to all that hard work, the program can now be used to perform useful tasks. The simplest application is printing notes.

By adding chord names and lyrics we obtain a lead sheet.

Polyphonic notation and piano music can also be printed. The following example combines some more exotic constructs.

The fragments shown above have all been written by hand, but that is not a requirement. Since the formatting engine is mostly automatic, it can serve as an output means for other programs that manipulate music. For example, it can also be used to convert databases of musical fragments to images for use on websites and multimedia presentations.

This manual also shows an application: the input format is text, and can

therefore be easily embedded in other text-based formats such as

LaTeX, HTML, or in the case of this manual, Texinfo. Using the

lilypond-book program, included with LilyPond, the input

fragments can be replaced by music images in the resulting PDF or HTML

output files. Another example is the third-party OOoLilyPond extension

for OpenOffice.org or LibreOffice, which makes it extremely easy to

embed musical examples in documents.

For more examples of LilyPond in action, full documentation, and the software itself, see our main website: www.lilypond.org.

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ Irodalomjegyzék >> ] |

| [ < Putting LilyPond to work ] | [Fel: A kottaszedés ] | [ Irodalomjegyzék > ] |

1.6 Engraved examples (BWV 861)

This section contains four reference engravings and two software-engraved versions of Bach’s Fugue in G minor from the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, BWV 861 (the last seven measures).

Bärenreiter BA5070 (Neue Ausgabe Sämtlicher Werke, Serie V, Band 6.1, 1989):

Bärenreiter BA5070 (Neue Ausgabe Sämtlicher Werke, Serie V, Band 6.1, 1989), an alternate musical source. Aside from the textual differences, this demonstrates slight variations in the engraving decisions, even from the same publisher and edition:

Breitkopf & Härtel, edited by Ferruccio Busoni (Wiesbaden, 1894), also available from the Petrucci Music Library (IMSLP #22081). The editorial markings (fingerings, articulations, etc.) have been removed for clearer comparison with the other editions here:

Bach-Gesellschaft edition (Leipzig, 1866), available from the Petrucci Music Library (IMSPL #02221):

Finale 2008:

LilyPond, version 2.23.82:

| [ << A kottaszedés ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ GNU Free Documentation License >> ] |

| [ < Engraved examples (BWV 861) ] | [Fel: Top ] | [ Short literature list > ] |

2. Irodalomjegyzék

Here are lists of references used in LilyPond.

| 2.1 Short literature list | ||

| 2.2 Long literature list |

| [ << Irodalomjegyzék ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ GNU Free Documentation License >> ] |

| [ < Irodalomjegyzék ] | [Fel: Irodalomjegyzék ] | [ Long literature list > ] |

2.1 Short literature list

If you need to know more about music notation, here are some interesting titles to read.

- Ignatzek 1995

Klaus Ignatzek, Die Jazzmethode für Klavier. Schott’s Söhne 1995. Mainz, Germany ISBN 3-7957-5140-3.

A tutorial introduction to playing Jazz on the piano. One of the first chapters contains an overview of chords in common use for Jazz music.

- Gerou 1996

Tom Gerou and Linda Lusk, Essential Dictionary of Music Notation. Alfred Publishing, Van Nuys CA ISBN 0-88284-768-6.

A concise, alphabetically ordered list of typesetting and music (notation) issues, covering most of the normal cases.

- Gould 2011

Elaine Gould, Behind Bars: the Definitive Guide to Music Notation. Faber Music Ltd. ISBN 0-571-51456-1.

Hals über Kopf: Das Handbuch des Notensatzes. Edition Peters. ISBN 1843670488.

A comprehensive guide to the rules and conventions of music notation. Covering everything from basic themes to complex techniques and providing a comprehensive grounding in notational principles.

- Read 1968

Gardner Read, Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice. Taplinger Publishing, New York (2nd edition).

A standard work on music notation.

- Ross 1987

Ted Ross, Teach yourself the art of music engraving and processing. Hansen House, Miami, Florida 1987.

This book is about music engraving, i.e., professional typesetting. It contains directions on stamping, use of pens and notational conventions. The sections on reproduction technicalities and history are also interesting.

- Schirmer 2001

The G.Schirmer/AMP Manual of Style and Usage. G.Schirmer/AMP, NY, 2001. (This book can be ordered from the rental department.)

This manual specifically focuses on preparing print for publication by Schirmer. It discusses many details that are not in other, normal notation books. It also gives a good idea of what is necessary to bring printouts to publication quality.

- Stone 1980

-

Kurt Stone, Music Notation in the Twentieth Century. Norton, New York 1980.

This book describes music notation for modern serious music, but starts out with a thorough overview of existing traditional notation practices.

| [ << Irodalomjegyzék ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ GNU Free Documentation License >> ] |

| [ < Short literature list ] | [Fel: Irodalomjegyzék ] | [ GNU Free Documentation License > ] |

2.2 Long literature list

University of Colorado Engraving music bibliography

- Willi Apel. The notation of polyphonic music, 900-1600. Cambridge, Mass, 1953. Musical notation.

- Ernest Austin. The Story of Music Printing. Lowe and Brydone Printers, Ltd., London. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Anna Maria Busse Berger. Mensuration and proportion signs : origins and evolution. Clarendon Press, Oxford, England, 1993. subject: early notation.

- Roger Bowers. Music & Letters, volume 73. August 1992. Some reflection upon notation and proportion in Monteverdi’s mass and vespers.

- Paul Brainard. Current Musicology. Number 50. July-Dec 1992. Proportional notation in the music of Schutz and his contemporaries in the 17th Century.

- Carl Brandt and Clinton Roemer. Standardized Chord Symbol Notation. Roerick Music Co., Sherman Oaks, CA. subject: musical notation.

- Earle Brown. Musical Quarterly, volume 72. Spring 1986. The notation and performance of new music.

- John Cage. Notations. Something Else Press, New York, 1969. Music, Manuscripts, Facsimiles. Facsimiles of holographs from the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, with text by 269 composers, but rearranged using chance operations.,V).

- J Carter. New Paths in Book Collecting. London, 1934. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- F. Chrsander. A Sketch of the HIstory of Music printing, from the 15th to the 16th century. 18??. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Henry Cowell. Our Inadequate Notation. Modern Music, 4(3), 1927. subject: 20th century notation.

- Henry Cowell. New Musical Resources. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, 1930. subject: 20th century notation.

- O.F. Deutsch. Music Publishers’ Numbers. London, 1946. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Suzanne Eggleston. Notes. New periodicals, 51(2):657(7), Dec 1994. A list of new music periodicals covering the period Jun.-Dec. 1994. Includes aims, formats and a description of the contents of each listed periodical. Includes Music Notation News.

- Hubert Foss. Music Printing. Practical Printing and Binding. Oldhams Press Ltd., Long Acre, London. subject: musical notation.

- Jean Charles Francois. Writing without representation, and unreadable notation.. Perspectives of New Music, 30(1):6(15), Winter 1992. subject: Modern music has outgrown notation. While the computer is used to write down music with accuracy never before achieved, the range of modern sounds has surpassed the relevance of the computer...

- David Fuller. The Journal of Musicology, volume 7. Winter 1989. Notes and inegales unjoined: defending a definition. (written-out inequalities in music notation).

- Virginia Gaburo. Notation. Lingua Press, La Jolla, California, 1977. A Lecture about notation, new ideas about.

- Keith A Hamel. A design for music editing and printing software based on notational syntax. Perspectives of New Music, 27(1):70(14), Winter 1989.

- Archibald Jacob. Musical handwriting : or, How to put music on paper : A handbook for all musicians, professional and amateur. Oxford University Press, London, 1947. subject: Musical notation.

- Harold M Johnson. How to write music manuscript an exercise-method handbook for the music student, copyist, arranger, composer, teacher. Carl Fischer, Inc., New York, 1946. subject: Musical notation –Handbooks, manuals.

- David Evan Jones. Perspectives of New Music. 1990. Speech extrapolated. (includes notation).

- H King. Four Hundred Years of Music Printing. London, 1964. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- A.H King. The 50th Anniversary of Music Printing. 1973.

- O Kinkeldey. Music And Music Printing in Incunabula. Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, xxvi:89-118, 1932. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- D.W. Krummel. Graphic Analysis in Application to Early American Engraved Music. Notes, xvi:213, 9 1958. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- D.W Krummel. Oblong Format in Early Music Books. The Library, 5th ser., xxvi:312, 1971. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Jeffrey Lependorf. ?. Perspectives of New Music, 27(2):232(20), Summer 1989. Contemporary notation for the shakuhachi: a primer for composers. (Tradition and Renewal in the Music of Japan).

- G.A Marco. The Earliest Music Printers of Continental Europe: a Checklist of Facsimiles Illustrating Their Work. Charlottesville, Virginia, 1962. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- K. Meyer and J O’Meara. The Printing of Music, 1473-1934. The Dolphin, ii:171–207, 1935. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Raymond Monelle. Comparative Literature, volume 41. Summer 1989. Music notation and the poetic foot.

- A Novello. Some Account of the Methods of Musick Printing, with Specimens of the Various Sizes of Moveable Types and of Other Matters. London, 1847. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- C.B Oldman. Collecting Musical First Editions. London, 1934. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Carl Parrish. The Notation of Medieval Music. Carl Fischer, Inc., New York, 1946. subject: early notation.

- Carl Parrish. The notation of medieval music. Norton, New York, 1957. Musical notation.

- Harry Patch. Genesis of a Music. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1949. subject: early notation.

- B Pattison. Notes on Early Music Printing. The Library, xix:389-421, 1939. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Sandra Pinegar. Current Musicology. Number 53. July 1993. The seeds of notation and music paleography.

- Richard Rastall. The notation of Western music : an introduction. St. Martin’s Press, New York, N.Y., 1982. Musical notation.

- Richard Rastall. Music & Letters, volume 74. November 1993. Equal Temperament Music Notation: The Ailler-Brennink Chromatic Notation. Results and Conclusions of the Music Notation Refor by the Chroma Foundation (book reviews).

- Howard Risatti. New Music Vocabulary. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Illinois, 1975. A Guide to Notational Signs for Contemporary Music.

- Donald W. Krummel \& Stanley Sadie. Music Printing & Publishing. Macmillan Press, 1990. subject: musical notation.

- Norman E Smith. Current Musicology. Number 45-47. Jan-Dec 1990. The notation of fractio modi.

- W Squire. Notes on Early Music Printing. Bibliographica, iii(99), 1897. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Robert Steele. The Earliest English Music Printing. London, 1903. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- Willy Tappolet. La Notation Musicale. Neuchâtel, Paris, 1947. subject: general notation.

- Leo Treitler. The Journal of Musicology, volume 10. Spring 1992. The unwritten and written transmission, of medieval chant and the start-up of musical notation. Notational practice developed in medieval music to address the written tradition for chant which interacted with the unwritten vocal tradition.

- unknown author. Pictorial History of Music Printing. H. and A. Selmer, Inc., Elhardt, Indiana. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

- M.L West. Music & Letters, volume 75. May 1994. The Babylonian musical notation and the Hurrian melodic texts. A new way of deciphering the ancient Babylonian musical notation.

- C.F. Abdy Williams. The Story of Notation. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1903. subject: general notation.

- Emmanuel Wintermitz. Musical Autographs from Monteverdi to Hindemith. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1955. subject: history of music printing and engraving.

Computer notation bibliography

- G. Assayaag and D. Timis. A Toolbox for music notation. In Proceedings of the 1986 International Computer Music Conference, 1986.

- M. Balaban. A Music Workstation Based on Multiple Hierarchical Views of Music. San Francisco, In Proceedings of the 1988 International Computer Music Conference, 1988.

- Alan Belkin. Macintosh Notation Software: Present and Future. Computer Music Journal, 18(1), 1994. Some music notation systems are analysed for ease of use, MIDI handling. The article ends with a plea for a standard notation format. HWN.

- Herbert Bielawa. Review of Sibelius 7. Computer Music Journal, 1993?. A raving review/tutorial of Sibelius 7 for Acorn. (And did they seriously program a RISC chip in ... assembler ?!) HWN.

- Dorothea Blostein and Lippold Haken. Justification of Printed Music. Communications of the ACM, J34(3):88-99, March 1991. This paper provides an overview of the algorithm used in LIME for spacing individual lines. HWN.

- Dorothea Blostein and Lippold Haken. The Lime Music Editor: A Diagram Editor Involving Complex Translations. Software Practice and Experience, 24(3):289–306, march 1994. A description of various conversions, decisions and issues relating to this interactive editor HWN.

- Nabil Bouzaiene, Loïc Le Gall, and Emmanuel Saint-James. Une bibliothèque pour la notation musicale baroque. LNCS. In EP ’98, 1998. Describes ATYS, an extension to Berlioz, that can mimick handwritten baroque style beams.

- Donald Byrd. A System for Music Printing by Computer. Computers and the Humanities, 8:161-72, 1974.

- Donald Byrd. Music Notation by Computer. PhD thesis, Indiana University, 1985. Describes the SMUT (sic) system for automated music printout.

- Donald Byrd. Music Notation Software and Intelligence. Computer Music Journal, 18(1):17–20, 1994. Byrd (author of Nightingale) shows four problematic fragments of notation, and rants about notation programs that try to exhibit intelligent behaviour. HWN.

- Walter B Hewlett and Eleanor Selfridge-Field. Directory of Computer Assisted Research in Musicology. . Annual editions since 1985, many containing surveys of music typesetting technology. SP.

- Alyssa Lamb. The University of Colorado Music Engraving page. 1996. Webpages about engraving (designed with finale users in mind) (sic) HWN.

- Roger B. Dannenberg. Music Representation: Issues, Techniques, and Systems. Computer Music Journal, 17(3), 1993. This article points to some problems and solutions with music representation. HWN.

- Michael Droettboom. Study of music Notation Description Languages. Technical Report, 2000. GUIDO and lilypond compared. LilyPond wins on practical issues as usability and availability of tools, GUIDO wins on implementation simplicity.

- R. F. Ericson. The DARMS Project: A status report. Computing in the humanities, 9(6):291–298, 1975. Gourlay [gourlay86] writes: A discussion of the design and potential uses of the DARMS music-description language.

- H.S. Field-Richards. Cadenza: A Music Description Language. Computer Music Journal, 17(4), 1993. A description through examples of a music entry language. Apparently it has no formal semantics. There is also no implementation of notation convertor. HWN.

- Miguel Filgueiras. Some Music Typesetting Algorithms. .

- Miguel Filgueiras and José Paulo Leal. Representation and manipulation of music documents in SceX. Electronic Publishing, 6(4):507–518, 1993.

- Miguel Filgueiras. Implementing a Symbolic Music Processing System. 1996.

- Eric Foxley. Music — A language for typesetting music scores. Software — Practice and Experience, 17(8):485-502, 1987. A paper on a simple TROFF preprocessor to typeset music.

- Loïc Le Gall. Création d’une police adaptée à la notation musicale baroque. Master’s thesis, École Estienne, 1997.

- Martin Gieseking. Code-basierte Generierung interaktiver Notengraphik. PhD thesis, Universität Osnabrück, 2001.

- David A. Gomberg. A Computer-Oriented System for Music Printing. PhD thesis, Washington University, 1975.

- David A. Gomberg. A Computer-oriented System for Music Printing. Computing and the Humanities, 11:63-80, march 1977. Gourlay [gourlay86] writes: "A discussion of the problems of representing the conventions of musical notation in computer algorithms.".

- John. S. Gourlay. A language for music printing. Communications of the ACM, 29(5):388–401, 1986. This paper describes the MusiCopy musicsetting system and an input language to go with it.

- John S. Gourlay, A. Parrish, D. Roush, F. Sola, and Y. Tien. Computer Formatting of Music. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-2/87-TR3, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. This paper discusses the development of algorithms for the formatting of musical scores (from abstract). It also appeared at PROTEXT III, Ireland 1986.

- John S. Gourlay. Spacing a Line of Music,. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-10/87-TR35, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987.

- John Grøver. A computer-oriented description of Music Notation. Part III: Accidental Positioning. Technical Report 135, Department of informatics, University of Oslo, 1989. Placement of accidentals crystallised in an enormous set of rules. Same remarks as for [grover89-twovoices] applies.

- John Grøver. A computer-oriented description of Music Notation. Part I. The Symbol Inventory. Technical Report 133, Department of informatics, University of Oslo, 1989. The goal of this series of reports is a full description of music formatting. As these largely depend on parameters of fonts, it starts with a verbose description of music symbols. The subject is treated backwards: from general rules of typesetting the author tries to extract dimensions for characters, whereas the rules of typesetting (in a particular font) follow from the dimensions of the symbols. His symbols do not match (the stringent) constraints formulated by eg. [wanske].

- John Grøver. A computer-oriented description of Music Notation. Part II: Two Voice Sharing a Staff, Leger Line Rules, Dot Positioning. Technical Report 134, Department of informatics, University of Oslo, 1989. A lot rules for what is in the title are formulated. The descriptions are long and verbose. The verbosity shows that formulating specific rules is not the proper way to approach the problem. Instead, the formulated rules should follow from more general rules, similar to [parrish87-simultaneities].

- Lippold Haken and Dorothea Blostein. The Tilia Music Representation: Extensibility, Abstraction, and Notation Contexts for the Lime Music Editor. Computer Music Journal, 17(3):43–58, 1993.

- Lippold Haken and Dorothea Blostein. A New Algorithm for Horizontal Spacing of Printed Music. Banff, In International Computer Music Conference, pages 118-119, Sept 1995. This describes an algorithm which uses springs between adjacent columns.

- Wael A. Hegazy. On the Implementation of the MusiCopy Language Processor,. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-10/87-TR34, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. Describes the "parser" which converts MusiCopy MDL to MusiCopy Simultaneities and columns. MDL is short for Music Description Language [gourlay86]. It accepts music descriptions that are organised into measures filled with voices, which are filled with notes. The measures can be arranged simultaneously or sequentially. To address the 2-dimensionality, almost all constructs in MDL must be labeled. MDL uses begin/end markers for attribute values and spanners. Rightfully the author concludes that MusiCopy must administrate a "state" variable containing both properties and current spanning symbols. MusiCopy attaches graphic information to the objects constructed in the input: the elements of the input are partially complete graphic objects.

- Wael A. Hegazy and John S. Gourlay. Optimal line breaking in music. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-8/87-TR33, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University,, 1987.

- Wael A. Hegazy and John S. Gourlay. (J. C. van Vliet, editor). Optimal line breaking in music. Cambridge University Press, In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Publishing, Document Manipulation and Typography. Nice (France), April 1988.

- Walter B. Hewlett and Eleanor Selfridge-Field, editors. The Virtual Score; representation, retrieval and restoration. Computing in Musicology. MIT Press, 2001.

- H. H. Hoos, K. A. Hamel, K. Renz, and J. Kilian. The GUIDO Music Notation Format—A Novel Approach for Adequately Representing Score-level Music. In Proceedings of International Computer Music Conference, pages 451–454, 1998.

- Peter S. Langston. Unix music tools at Bellcore. Software — Practice and Experience, 20(S1):47–61, 1990. This paper deals with some command-line tools for music editing and playback.

- Dominique Montel. La gravure de la musique, lisibilité esthétique, respect de l’oevre. Lyon, In Musique \& Notations, 1997.

- Giovanni Müller. Interaktive Bearbeitung konventioneller Musiknotation. PhD thesis, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zürich, 1990. This is about engraver-quality typesetting with computers. It accepts the axiom that notation is too difficult to generate automatically. The result is that a notation program should be a WYSIWYG editor that allows one to tweak everything.

- Han Wen Nienhuys and Jan Nieuwenhuizen. LilyPond, a system for automated music engraving. Firenze, In XIV Colloquium on Musical Informatics, pages 167–172, May 2003.

- Cindy Grande. NIFF6a Notation Interchange File Format. Grande Software Inc., 1995. Specs for NIFF, a reasonably comprehensive but binary format for notation HWN.

- Severo M. Ornstein and John Turner Maxwell III. Mockingbird: A Composer’s Amanuensis. Technical Report CSL-83-2, Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, 3333 Coyote Hill Road, Palo Alto, CA, 94304, January 1983.

- Severo M. Ornstein and John Turner Maxwell III. Mockingbird: A Composer’s Amanuensis. Byte, 9, January 1984. A discussion of an interactive and graphical computer system for music composition.

- Stephen Dowland Page. Computer Tools for Music Information Retrieval. PhD thesis, Dissertation University of Oxford, 1988. Don’t ask Stephen for a copy. Write to the Bodleian Library, Oxford, or to the British Library, instead. SP.

- Allen Parish, Wael A. Hegazy, John S. Gourlay, Dean K. Roush, and F. Javier Sola. MusiCopy: An automated Music Formatting System. Technical Report, 1987.

- A. Parrish and John S. Gourlay. Computer Formatting of Musical Simultaneities,. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-10/87-TR28, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. This note discusses placement of balls, stems, dots which occur at the same moment ("Simultaneity").

- Steven Powell. Music engraving today. Brichtmark, 2002. A "How Steven uses Finale" manual.

- Gary M. Rader. Creating Printed Music Automatically. Computer, 29(6):61–69, June 1996. Describes a system called MusicEase, and explains that it uses "constraints" (which go unexplained) to automatically position various elements.

- Kai Renz. Algorithms and data structures for a music notation system based on GUIDO music notation. PhD thesis, Universität Darmstadt, 2002.

- René Roelofs. Een Geautomatiseerd Systeem voor het Afdrukken van Muziek. Number 45327. Master’s thesis, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, 1991. This dutch thesis describes a monophonic typesetting system, and focuses on the breaking algorithm, which is taken from Hegazy & Gourlay.

- Joseph Rothstein. Review of Passport Designs’ Encore Music Notation Software. Computer Music Journal, ?.

- Dean K. Roush. Using MusiCopy. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-18/87-TR31, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. User manual of MusiCopy.

- D. Roush. Music Formatting Guidelines. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-3/88-TR10, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1988. Rules on formatting music formulated for use in computers. Mainly distilled from [Ross] HWN.

- Eleanor Selfridge-Field, editor. Beyond MIDI: the handbook of musical codes. MIT Press, 1997. A description of various music interchange formats.

- Donald Sloan. Aspects of Music Representation in HyTime/SMDL. Computer Music Journal, 17(4), 1993. An introduction into HyTime and its score description variant SMDL. With a short example that is quite lengthy in SMDL.

- International Organization for Standardization~(ISO). Information Technology - Document Description and Processing Languages - Standard Music Description Language (SMDL). Number ISO/IEC DIS 10743. 1992.

- Leland Smith. Editing and Printing Music by Computer, volume 17. 1973. Gourlay [gourlay86] writes: A discussion of Smith’s music-printing system SCORE.

- F. Sola. Computer Design of Musical Slurs, Ties and Phrase Marks,. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-10/87-TR32, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. Overview of a procedure for generating slurs.

- F. Sola and D. Roush. Design of Musical Beams,. Technical Report OSU-CISRC-10/87-TR30, Department of Computer and Information Science, The Ohio State University, 1987. Calculating beam slopes HWN.

- Howard Wright. how to read and write tab: a guide to tab notation. . FAQ (with answers) about TAB, the ASCII variant of Tablature. HWN.

- Geraint Wiggins, Eduardo Miranda, Alaaaan Smaill, and Mitch Harris. A Framework for the evaluation of music representation systems. Computer Music Journal, 17(3), 1993. A categorisation of music representation systems (languages, OO systems etc) split into high level and low level expressiveness. The discussion of Charm and parallel processing for music representation is rather vague. HWN.

Engraving bibliography

- Harald Banter. Akkord Lexikon. Schott’s Söhne, Mainz, Germany, 1987. Comprehensive overview of commonly used chords. Suggests (and uses) a unification for all different kinds of chord names.

- A Barksdale. The Printed Note: 500 Years of Music Printing and Engraving. The Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio, January 1957. ‘The exhibition "The Printed Note" attempts to show the various processes used since the second of the 15th century for reproducing music mechanically ... ’. The illustration mostly feature ancient music.

- Laszlo Boehm. Modern Music Notation. G. Schirmer, Inc., New York, 1961. Heussenstamm writes: A handy compact reference book in basic notation.

- H. Elliot Button. System in Musical Notation. Novello and co., London, 1920.

- Herbert Chlapik. Die Praxis des Notengraphikers. Doblinger, 1987. An clearly written book for the casually interested reader. It shows some of the conventions and difficulties in printing music HWN.

- Anthony Donato. Preparing Music Manuscript. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1963.

- Donemus. Uitgeven van muziek. Donemus Amsterdam, 1982. Manual on copying for composers and copyists at the Dutch publishing house Donemus. Besides general comments on copying, it also contains a lot of hands-on advice for making performance material for modern pieces.

- William Gamble. Music Engraving and printing. Historical and Technical Treatise. Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, ltd., 1923. This patriotic book was an attempt to promote and help British music engravers. It is somewhat similar to Hader’s book [hader48] in scope and style, but Gamble focuses more on technical details (Which French punch cutters are worth buying from, etc.), and does not treat typographical details, such as optical illusions. It is available as reprint from Da Capo Press, New York (1971).

- Tom Gerou and Linda Lusk. Essential Dictionary of Music Notation. Alfred Publishing, Van Nuys CA, 1996. A cheap, concise, alphabetically ordered list of typesetting and music (notation) issues with a rather simplistic attitude but in most cases "good-enough" answers JCN.

- Elaine Gould. Behind Bars. Faber Music Ltd., 2011. A comprehensive guide to the rules and conventions of music notation. Covering everything from basic themes to complex techniques and providing a comprehensive grounding in notational principles.

- Elaine Gould. Hals über Kopf. Edition Peters, 2014. Ein vollständiges Regelwerk für den Modernen Notensatz auf höchstem Niveau, ein Meilenstein der Notationskunde und ein Leitfaden für jeden Musiker, der sich auf diesem Gebiet umfassende Kenntnisse aneignen möchte.

- Karl Hader. Aus der Werkstatt eines Notenstechers. Waldheim–Eberle Verlag, Vienna, 1948. Hader was a chief-engraver in a Viennese engraving workshop. This beautiful booklet was intended as an introduction for laymen on the art of engraving. It contains a step by step, in-depth explanation of how to cut and stamp music into zinc plates. It also contains a few compactly formulated rules on musical orthography. Out of print.

- George Heussenstamm. The Norton Manual of Music Notation. Norton, New York, 1987. Hands-on instruction book for copying (ie. handwriting) music. Fairly complete. HWN.

- Klaus Ignatzek. Die Jazzmethode für Klavier 1. Schott, 1995. This book contains a system for denoting chords that is used in LilyPond.

- Andreas Jaschinski, editor. Notation. Number BVK1625. Bärenreiter Verlag, 2000.

- Harold Johnson. How to write music manuscript. Carl Fischer, Inc., New York, 1946.

- Erdhard Karkoshka. Notation in New Music; a critical guide to interpretation and realisation. Praeger Publishers, New York, 1972. (Out of print).

- Mark Mc Grain. Music notation. Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation, 1991. HWN writes: ‘Book’ edition of lecture notes from XXX school of music. The book looks like it is xeroxed from bad printouts. The content has nothing you won’t find in other books like [read] or [heussenstamm].

- mpa. Standard music notation specifications for computer programming.. MPA, December 1996. Pamphlet explaining a few fine points in music font design HWN.

- Richard Rastall. The Notation of Western Music: an Introduction. J. M. Dent \& Sons London, 1983. Interesting account of the evolution and origin of common notation starting from neumes, and ending with modern innovations HWN.

- Gardner Read. Modern Rhythmic Notation. Indiana University Press, 1978. Sound (boring) review of the various hairy rhythmic notations used by avant-garde composers HWN.

- Gardner Read. Music Notation: a Manual of Modern Practice. Taplinger Publishing, New York, 1979. This is as close to the “standard” reference work for music notation issues as one is likely to get.

- Clinton Roemer. The Art of Music Copying. Roerick music co., Sherman Oaks (CA), 2nd edition, 1984. Out of print. Heussenstamm writes: an instructional manual which specializes in methods used in the commercial field.

- Glen Rosecrans. Music Notation Primer. Passantino, New York, 1979. Heussenstamm writes: Limited in scope, similar to [Roemer84].

- Carl A Rosenthal. A Practical Guide to Music Notation. MCA Music, New York, 1967. Heussenstamm writes: Informative in terms of traditional notation. Does not concern score preparation.

- Ted Ross. Teach yourself the art of music engraving and processing. Hansen House, Miami, Florida, 1987.

- Schirmer. The G. Schirmer Manual of Style and Usage. The G. Schirmer Publications Department, New York, 2001. This is the style guide for Schirmer publications. This manual specifically focuses on preparing print for publication by Schirmer. It discusses many details that are not in other, normal notation books. It also gives a good idea of what is necessary to bring printouts to publication quality. It can be ordered from the rental department.

- Kurt Stone. Music Notation in the Twentieth Century. Norton, New York, 1980. Heussenstamm writes: The most important book on notation in recent years.

- Börje Tyboni. Noter Handbok I Traditionell Notering. Gehrmans Musikförlag, Stockholm, 1994. Swedish book on music notation.

- Albert C. Vinci. Fundamentals of Traditional Music Notation. Kent State University Press, 1989.

- Helene Wanske. Musiknotation — Von der Syntax des Notenstichs zum EDV-gesteuerten Notensatz. Schott-Verlag, Mainz, 1988.

- Maxwell Weaner and Walter Boelke. Standard Music Notation Practice. Music Publisher’s Association of the United States Inc, New York, 1993.

- Johannes Wolf. Handbuch der Notationskunde. Breitkopf & Hartel, Leipzig, 1919. Very thorough treatment (in two volumes) of the history of music notation.

| [ << Irodalomjegyzék ] | [Címoldal][Tartalom][Tárgymutató] | [ LilyPond tárgymutató >> ] |

| [ < Long literature list ] | [Fel: Top ] | [ LilyPond tárgymutató > ] |

A. GNU Free Documentation License

Version 1.3, 3 November 2008

Copyright © 2000, 2001, 2002, 2007, 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc. https://fsf.org/ Everyone is permitted to copy and distribute verbatim copies of this license document, but changing it is not allowed. |

-

PREAMBLE

The purpose of this License is to make a manual, textbook, or other functional and useful document free in the sense of freedom: to assure everyone the effective freedom to copy and redistribute it, with or without modifying it, either commercially or noncommercially. Secondarily, this License preserves for the author and publisher a way to get credit for their work, while not being considered responsible for modifications made by others.

This License is a kind of “copyleft”, which means that derivative works of the document must themselves be free in the same sense. It complements the GNU General Public License, which is a copyleft license designed for free software.

We have designed this License in order to use it for manuals for free software, because free software needs free documentation: a free program should come with manuals providing the same freedoms that the software does. But this License is not limited to software manuals; it can be used for any textual work, regardless of subject matter or whether it is published as a printed book. We recommend this License principally for works whose purpose is instruction or reference.

-

APPLICABILITY AND DEFINITIONS

This License applies to any manual or other work, in any medium, that contains a notice placed by the copyright holder saying it can be distributed under the terms of this License. Such a notice grants a world-wide, royalty-free license, unlimited in duration, to use that work under the conditions stated herein. The “Document”, below, refers to any such manual or work. Any member of the public is a licensee, and is addressed as “you”. You accept the license if you copy, modify or distribute the work in a way requiring permission under copyright law.

A “Modified Version” of the Document means any work containing the Document or a portion of it, either copied verbatim, or with modifications and/or translated into another language.

A “Secondary Section” is a named appendix or a front-matter section of the Document that deals exclusively with the relationship of the publishers or authors of the Document to the Document’s overall subject (or to related matters) and contains nothing that could fall directly within that overall subject. (Thus, if the Document is in part a textbook of mathematics, a Secondary Section may not explain any mathematics.) The relationship could be a matter of historical connection with the subject or with related matters, or of legal, commercial, philosophical, ethical or political position regarding them.

The “Invariant Sections” are certain Secondary Sections whose titles are designated, as being those of Invariant Sections, in the notice that says that the Document is released under this License. If a section does not fit the above definition of Secondary then it is not allowed to be designated as Invariant. The Document may contain zero Invariant Sections. If the Document does not identify any Invariant Sections then there are none.

The “Cover Texts” are certain short passages of text that are listed, as Front-Cover Texts or Back-Cover Texts, in the notice that says that the Document is released under this License. A Front-Cover Text may be at most 5 words, and a Back-Cover Text may be at most 25 words.

A “Transparent” copy of the Document means a machine-readable copy, represented in a format whose specification is available to the general public, that is suitable for revising the document straightforwardly with generic text editors or (for images composed of pixels) generic paint programs or (for drawings) some widely available drawing editor, and that is suitable for input to text formatters or for automatic translation to a variety of formats suitable for input to text formatters. A copy made in an otherwise Transparent file format whose markup, or absence of markup, has been arranged to thwart or discourage subsequent modification by readers is not Transparent. An image format is not Transparent if used for any substantial amount of text. A copy that is not “Transparent” is called “Opaque”.

Examples of suitable formats for Transparent copies include plain ASCII without markup, Texinfo input format, LaTeX input format, SGML or XML using a publicly available DTD, and standard-conforming simple HTML, PostScript or PDF designed for human modification. Examples of transparent image formats include PNG, XCF and JPG. Opaque formats include proprietary formats that can be read and edited only by proprietary word processors, SGML or XML for which the DTD and/or processing tools are not generally available, and the machine-generated HTML, PostScript or PDF produced by some word processors for output purposes only.

The “Title Page” means, for a printed book, the title page itself, plus such following pages as are needed to hold, legibly, the material this License requires to appear in the title page. For works in formats which do not have any title page as such, “Title Page” means the text near the most prominent appearance of the work’s title, preceding the beginning of the body of the text.

The “publisher” means any person or entity that distributes copies of the Document to the public.

A section “Entitled XYZ” means a named subunit of the Document whose title either is precisely XYZ or contains XYZ in parentheses following text that translates XYZ in another language. (Here XYZ stands for a specific section name mentioned below, such as “Acknowledgements”, “Dedications”, “Endorsements”, or “History”.) To “Preserve the Title” of such a section when you modify the Document means that it remains a section “Entitled XYZ” according to this definition.

The Document may include Warranty Disclaimers next to the notice which states that this License applies to the Document. These Warranty Disclaimers are considered to be included by reference in this License, but only as regards disclaiming warranties: any other implication that these Warranty Disclaimers may have is void and has no effect on the meaning of this License.

-

VERBATIM COPYING

You may copy and distribute the Document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this License, the copyright notices, and the license notice saying this License applies to the Document are reproduced in all copies, and that you add no other conditions whatsoever to those of this License. You may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies you make or distribute. However, you may accept compensation in exchange for copies. If you distribute a large enough number of copies you must also follow the conditions in section 3.

You may also lend copies, under the same conditions stated above, and you may publicly display copies.

-

COPYING IN QUANTITY

If you publish printed copies (or copies in media that commonly have printed covers) of the Document, numbering more than 100, and the Document’s license notice requires Cover Texts, you must enclose the copies in covers that carry, clearly and legibly, all these Cover Texts: Front-Cover Texts on the front cover, and Back-Cover Texts on the back cover. Both covers must also clearly and legibly identify you as the publisher of these copies. The front cover must present the full title with all words of the title equally prominent and visible. You may add other material on the covers in addition. Copying with changes limited to the covers, as long as they preserve the title of the Document and satisfy these conditions, can be treated as verbatim copying in other respects.

If the required texts for either cover are too voluminous to fit legibly, you should put the first ones listed (as many as fit reasonably) on the actual cover, and continue the rest onto adjacent pages.

If you publish or distribute Opaque copies of the Document numbering more than 100, you must either include a machine-readable Transparent copy along with each Opaque copy, or state in or with each Opaque copy a computer-network location from which the general network-using public has access to download using public-standard network protocols a complete Transparent copy of the Document, free of added material. If you use the latter option, you must take reasonably prudent steps, when you begin distribution of Opaque copies in quantity, to ensure that this Transparent copy will remain thus accessible at the stated location until at least one year after the last time you distribute an Opaque copy (directly or through your agents or retailers) of that edition to the public.

It is requested, but not required, that you contact the authors of the Document well before redistributing any large number of copies, to give them a chance to provide you with an updated version of the Document.

-

MODIFICATIONS

You may copy and distribute a Modified Version of the Document under the conditions of sections 2 and 3 above, provided that you release the Modified Version under precisely this License, with the Modified Version filling the role of the Document, thus licensing distribution and modification of the Modified Version to whoever possesses a copy of it. In addition, you must do these things in the Modified Version:

- Use in the Title Page (and on the covers, if any) a title distinct from that of the Document, and from those of previous versions (which should, if there were any, be listed in the History section of the Document). You may use the same title as a previous version if the original publisher of that version gives permission.

- List on the Title Page, as authors, one or more persons or entities responsible for authorship of the modifications in the Modified Version, together with at least five of the principal authors of the Document (all of its principal authors, if it has fewer than five), unless they release you from this requirement.

- State on the Title page the name of the publisher of the Modified Version, as the publisher.

- Preserve all the copyright notices of the Document.

- Add an appropriate copyright notice for your modifications adjacent to the other copyright notices.

- Include, immediately after the copyright notices, a license notice giving the public permission to use the Modified Version under the terms of this License, in the form shown in the Addendum below.

- Preserve in that license notice the full lists of Invariant Sections and required Cover Texts given in the Document’s license notice.

- Include an unaltered copy of this License.

- Preserve the section Entitled “History”, Preserve its Title, and add to it an item stating at least the title, year, new authors, and publisher of the Modified Version as given on the Title Page. If there is no section Entitled “History” in the Document, create one stating the title, year, authors, and publisher of the Document as given on its Title Page, then add an item describing the Modified Version as stated in the previous sentence.

- Preserve the network location, if any, given in the Document for public access to a Transparent copy of the Document, and likewise the network locations given in the Document for previous versions it was based on. These may be placed in the “History” section. You may omit a network location for a work that was published at least four years before the Document itself, or if the original publisher of the version it refers to gives permission.

- For any section Entitled “Acknowledgements” or “Dedications”, Preserve the Title of the section, and preserve in the section all the substance and tone of each of the contributor acknowledgements and/or dedications given therein.

- Preserve all the Invariant Sections of the Document, unaltered in their text and in their titles. Section numbers or the equivalent are not considered part of the section titles.

- Delete any section Entitled “Endorsements”. Such a section may not be included in the Modified Version.

- Do not retitle any existing section to be Entitled “Endorsements” or to conflict in title with any Invariant Section.

- Preserve any Warranty Disclaimers.

If the Modified Version includes new front-matter sections or appendices that qualify as Secondary Sections and contain no material copied from the Document, you may at your option designate some or all of these sections as invariant. To do this, add their titles to the list of Invariant Sections in the Modified Version’s license notice. These titles must be distinct from any other section titles.

You may add a section Entitled “Endorsements”, provided it contains nothing but endorsements of your Modified Version by various parties—for example, statements of peer review or that the text has been approved by an organization as the authoritative definition of a standard.